Hometown Hero

Detroit did not come to my mind as a bucket list destination.

But it was the perfect starting point for our next trip. My husband Richard was born in the Upper Peninsula, making him a Yooper, but I had never been. We decided to explore this area that so many American musicians, artists, writers, industrialists, and architects called home — the upper Midwest.

The itinerary: Henry Ford, Bob Dylan, Ernest Hemingway, Prince, and Eminem, among others. We took a direct flight from Savannah to Detroit.

“Honey, is it safe for us to go there?” I asked.

“Detroit?” he asked. “You’re afraid of a city?”

“Well, there is a lot of poverty and crime,” I replied. “And there were riots.”

“Wendy, the riots were decades ago. In the ’60s,” he replied.

I pulled up the Detroit Historical Society website on my phone and began reading about the Uprising of 1967. It started on a sweltering July evening after police raided a bar on 12th Street.

A brick thrown through a police cruiser window lit the tinder box. Decades of frustration over harsh law enforcement tactics, segregation, and economic inequality erupted into five days of rioting, looting, and arson.

It was considered one of the largest instances of civil unrest in twentieth century America. Over 1,000 people were injured and 43 people killed, mostly by law enforcement.

As I continued to read, I learned that Detroit was never the same — white flight that occurred after the riots left the city deeply segregated and in economic ruin.

That was right around the time the movie Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner was released. I remembered my parents being disturbed by it; their views reflecting the times we lived in.

And it was during that period when Mom got so angry with me, I thought.

“Did I tell you that I was in the Civil Air Patrol?” I asked Richard, ready to tell him the story. By now, he had figured out the Apple Air Play on the blue SUV rental, and I had found the air conditioning — a non-negotiable for hormonally challenged women like me.

“Yes,” he said, his attention fully focused on navigating unfamiliar streets. Of course I had.

Stand by me

I rested my head against the window. Looking out, I saw the blur of suburban black box strip malls and newer neighborhoods as we sped down the interstate.

My mind drifted back to being fourteen.

I remembered walking through the white painted wooden doors of the American Legion. Senior C.A.P. cadets were hosting a kick-off mixer for curious high school students. I turned to wave to my mom who had just dropped me off. She blew me a kiss.

Inside, I was greeted by the smell of warm pizza. I loosened my periwinkle corduroy jacket and threw it onto a pile near the door. The main hall was dim, but light from a small corner kitchen spilled onto the small parquet dance floor, allowing one’s eyes to adjust.

Shiny gold and ultramarine balloons floated near the ceiling, tethered together by navy and yellow crepe paper.

I walked across the dance floor, batting away a loose balloon. A couple of my girlfriends were gathered to one corner of the room, giggling and staring at a few boys who sat in folded chairs on the opposite side.

“Dancing in the Street” by Martha Reeves and the Vandellas blared from the tabletop speakers. “Okay, everyone, grab somebody, and let’s dance!” shouted one of the chaperones.

No one got up. I looked at my friends. Arms entwined, they looked over to the boys.

My mom had always encouraged us to speak up and get involved.

“Don’t be a wallflower,” she would say. “And be nice to everyone.”

I encouraged my friends to start dancing. Two, three, four songs came and went. Sweat began to trickle down my back; my face flushed. Finally, we ran over to the boys and led them to the floor.

Laughing and clapping, we were all in a line dancing. I looked over to the food table and saw a thin, shy boy dressed in a plaid button-down shirt and white Wrangler jeans slumped in a metal chair. Alone. He was in my English class and, like me, a bit dorky.

I waved to him. His eyes opened wide. I wasn’t sure if it was surprise or terror. “Come on,” I mouthed, and gestured him to join the dance floor.

I didn’t think of it as a brave moment. I was just following my mother’s prompt to be nice. I ran over, took his arm, and dragged him to the pine floor.

“I don’t know how to dance!” he exclaimed, pulling against my hand.

“It’s okay!” I shouted over the music. “None of us do!”

Grinning, his arms started doing some kind of motion that looked like he was washing clothes. Other kids joined in.

And before we knew it — the mixer was over. I picked up a blue balloon and grabbed the arm of my girlfriend, Nancy. We looked at each other, exhausted, but giggling.

After we jumped into Nancy’s car, her mom wanted to know all the details. We told her excitedly, talking over each other.

Driving up the dirt lane to our farmhouse, Mrs. Carter said softly, “Wendy, I hope everything goes okay for you.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Carter,” I said. “It was fun! And thank you for dropping me off!”

The screen door opened before I reached it. Mom stared at me, hairbrush in hand.

“Who did you dance with?” she immediately asked.

My mind went blank. Mouth dry. Fear grabbed my throat. “Don’t lie to me, Wendy,” she growled. “I got a phone call.”

“Everybody. Nobody.” I stuttered, bewildered.

“You were dancing with a colored boy,” she growled.

I stiffened, knowing what was coming next …

Not all heroes wear capes

Richard’s touch on my arm pulled me to the present.

“Hey, you?” Richard said gently. “We are almost at the hotel.”

“Sorry, honey,” I said. “I’m here.”

We spent several days in Detroit, trying to make sense of the city.

Touring Berry Gordie’s Motown and Aretha Franklin’s home and final resting place, we also enjoyed a Tiger’s game and walked through new up-and-coming neighborhoods, full of contemporary high-rises and franchised shops. We filled our souls with art and history, and our bellies with Detroit-style pizza and Midwestern steaks.

And we drove through bulldozed-out historic communities peppered with quaint 1920s bungalows and late Victorians. Most of them were standing alone, joined by vacant grassy lots that once held their next-door neighbors’ homes. One of these was the site of Eminem’s boyhood home. Though his house had been razed, an outdoor green space had been created in its place.

On our last day there, Richard wanted to stop and snap a photo of the iconic Eminem mural. Off of Rivard Street, there were no signs leading to it.

“Sure you want to find this?” I asked, feeling anxious in yet another part of Detroit.

“Yep, it’ll only take a minute,” he replied.

We found it. Turning into a parking lot behind a weathered brick building, we drove into a lot surrounded by a 12-foot-high chain link fence — the type commonly seen in prisons. Two elderly men in ripped jeans and frayed overcoats sat on a cracked sidewalk across the street.

My leg started jiggling.

We looked up, shading our eyes from the sun. There was a twenty-foot-tall Eminem. The mural depicted the ground-breaking rap star front and center, his white face and beige hoodie in stark contrast to the images of his D12 hip hop crew.

Richard got out to view the mural in more detail. I sat in the car and watched him, splitting open a sugary moist blueberry muffin from the hotel’s breakfast bar.

He jumped back in the car and headed up a cramped alley to the right of the building.

“Honey, there is no way out and nowhere to turn,” I said, spilling tepid coffee on my jeans.

“Just a minute, I want to see what this building is,” he replied.

Richard, having written guidebooks as well as being a journalist, is not afraid. His curiosity and enthusiasm for finding new adventures takes me, his loyal but anxious companion, to some “off the grid” places. This looked like one of them to me.

I looked in the side view mirror to see what the two men were doing. Still sitting, they were sharing something wrapped in aluminum foil.

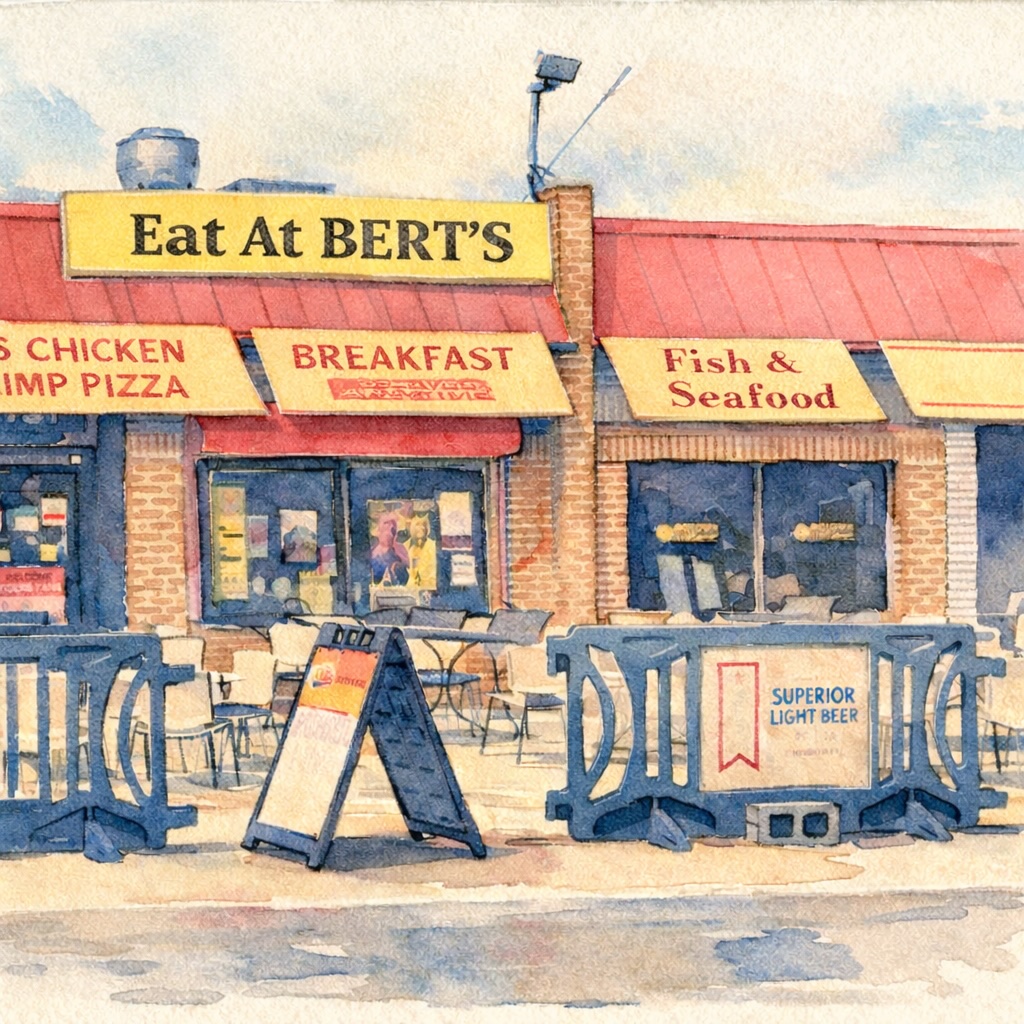

Our car nearly scraping the metal fence, we spied another mural on the side of the building. Faded, and barely discernible images of famous black jazz musicians were brushed on the wall. “Bert’s Warehouse Museum” was painted above them.

Snapping a picture from the driver’s seat, Richard put the car in reverse and threaded it back through the alley.

“Honey, honey, honey,” I said in rapid succession, rotating my hands in backwards circles, indicating stop.

“I used to park cars for a living,” he said with a grin. This is his standard refrain when he is behind the wheel, and I’m “helping” him with driving instructions — or when I’ve run out of my lorazepam.

We escaped from the parking pen and drove around to Russell Street to see the front of the building. Richard pulled into an empty space on the deserted street. We realized we were in the Eastern Market district of Detroit.

Multiple aluminum picnic tables with brightly colored umbrellas sat on the sidewalk in front of the building. “Eat at Bert’s” was painted in goldenrod and black, affixed to a crimson metal awning.

“Let’s go in,” Richard said, already unbuckling his seat belt.

My stomach dropped; however, I had learned that he usually finds some new adventure, and it was better to swallow my anxiety and experience it first-hand than be told about it later.

We stopped outside to see if their business hours were posted. The door suddenly opened and a slight, gray-haired man appeared.

“Oh!” I uttered in surprise.

“Come on in!” he said, opening the door wider for us.

We walked in. There were no customers. One side looked like a deli, the other had booths. Empty cardboard boxes emblazoned with liquor logos lined one wall.

Playing it forward

“We are just looking around,” Richard said. “Wow! What is this place?”

“This is where you can get great barbeque and Southern cooking,” the man said. “Or see a great show.”

“Can I get you something to eat?” he asked. He was thin, his face wrinkled with time and experience. His eyes were the color of Earl Grey tea. I stepped back. It felt like he knew me.

It was noon, and yet there was no one around. It dawned on me that he didn’t ask us if we wanted to order food. He asked if he could get us something to eat.

Just like my mom would say if a guest came to our house.

“Would you like to see the place?” he asked.

“Sure!” said Richard enthusiastically.

“Follow me,” he said.

We strolled through faded curtains to a dark, vacuous room filled with round tables and white chairs. It opened into an expanse of a showroom. Ebony walls, a stage, and glass mirrored balls filled the space.

“We had a big event in here last night,” he said. “Just breaking it down. We call this the Warehouse.”

“Let me show you this,” he said, raising his palm to lead the way.

We shuffled into a narrow hallway. Several large murals filled the uneven walls, the artist’s name, Curtis Lewis, boldly written on each corner. I immediately recognized the images of Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder.

“I know them!” I exclaimed.

“Yep,” said the man. “This is what Detroit brought to the world. ’Retha, Stevie, Prince, and lots of others.”

“This is so cool,” I said. “What is this mural?” pointing to another wall.

“The Brown Bomber. Joe Louis. Yeah, he grew up in Detroit.”

We meandered through the hall marveling at the memorabilia and art.

“Yep, I want this place to show black history. Tell our story. We get people from all over the world,” he said as we continued through the venue.

“Lots of greats used to come here. Stevie, Gladys, Marvin … they all played here. Kids still do. Even now, they play the clubs, then come back here ‘round midnight, and start jammin’. They’ll be coming tonight, if you’d like to come back.”

“Thanks, but unfortunately, we have to get on the road,” said Richard. “Next time?”

“What’s in here?” I asked, a door leading into another room.

“Oh, that’s the Jazz Club. The booths are original,” he said.

“How long have you been working here?” I asked.

The man chuckled. “Since it opened.”

It dawned on me. “You are … the owner?”

“That’s me, Bert,” he said. “Grew up here. Started this place in the ’80s. Raised my kids right here in Detroit. It’s a family business. Kids, wife, cousin.”

He opened a swinging door. Walking in was like time travel. Old leather bench seats with linoleum topped tables were separated by boards to create separate booths. A long bar filled the opposite wall. A small corner stage was ready for that night’s jazz trio, drum kit in place.

A hint of cigarette smoke clung to the walls. We exited another door and found our way back to the entrance.

“We need to be going,” said Richard. “Bert. Thank you. It was very generous of you to take us around. Next time we are in Detroit, we are coming back. Mind if I get a picture of you and Wendy?”

“Not at all,” he said. “Sure I can’t fix you something to eat?” he asked again.

We shook our heads. He curled his arm around my shoulder. Just like an old friend. I thanked him for taking time to bring a couple of strangers for a tour.

My heart felt full. This man, a holder of history. “Could I give you a hug?” I asked spontaneously. He held out his arms.

“No problem at all,” he said.

We drove off, heading out of the city.

I thought about ordinary heroes. They are everywhere.

I was raised to see difference as danger. But that mindset can be overcome. Understanding that bravery often comes in the small gestures. An invitation. A conversation. An open door. A full plate. A dance. A hug.

Detroit was what I expected. And nothing like what I expected.